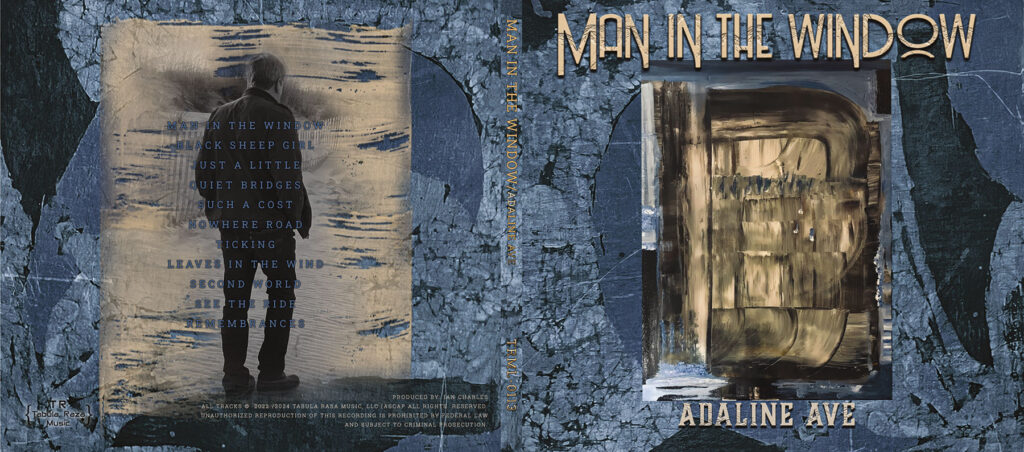

If you were to pitch the story of Man in the Window’s Adaline Ave to Hollywood producers, they might laugh you right out of the room over the implausibility of your tale. Reeling from the death of his wife and partner at the age of 16, a grieving 60-something corrections social worker who had never written a song and had only ever played his 1921 Steinway for family seeks out the services of a physical trainer. The PT he chooses happens to be a disillusioned music lifer with four decades of songwriting, performing, and production experience in his rearview mirror. As their friendship develops, the former suddenly finds himself writing the songs his wife had always urged him to write about their shared life while the latter lays aside his jaded weariness of music and begins to imagine what could be.

Steeped in the rich tradition of ‘70s piano pop and in that decade’s penchant for conceptually unified albums as well, Adaline Ave presents the listener with a strikingly paradoxical experience. It’s hard to imagine a more direct expression of grieving or a more authentic and unlikely testament to grief’s redemptive and generative properties. On the other hand, driven by joyful experimentation and what-ifs, blossoming parallel to the friendship between Pete Loss and producer/arranger/multi-instrumentalist Ian Charles, Adaline Ave achieves a homespun, sprawling studio grandeur. It is an unpremeditated epic, equal parts first-voice innocence and vivid imagination marked by bold production choices and stylistic savvy.